More Retailers Are Offering Buy Now, Pay Later Options. For Shoppers, It Comes with Risk

Angela Olaguera-Corcoran had long admired the handcrafted gold filigree earrings from Cambio & Co., a Canadian small business that works with artists in the Philippines. She saw the earrings as a connection to her family’s heritage, and she liked the idea of supporting an independent, women-run business. But the price-tag was just out of reach—until, during the pandemic, the business started using the buy now, pay later, or BNPL, provider Sezzle.

“I wasn’t able to drop $200 at a time, but I could break that up into payments of $50 [every] two weeks,” she says. “It made these pieces more affordable and accessible to me.”

Olaguera-Corcoran is one of the 30 per cent of Canadians who are comfortable using BNPL for an online purchase. BNPL installment plans—a form of loan that allows consumers to break up one purchase into a series of smaller, interest-free payments over a set period of time—rapidly grew in popularity during the pandemic alongside the broader e-commerce boom. But while they’re an increasingly common payment option for retailers across Canada, experts say they pose risks, like encouraging debt and overspending to shoppers—especially younger ones who may have less financial knowledge.

The rise of buy now, pay later platforms

The BNPL trend started with Australian fintech company Afterpay in 2014, and has since boosted the fortunes of a growing number of start-ups. In 2017, Canada’s first BNPL platform PayBright launched in the country and international companies soon entered the market: Minneapolis-headquartered Sezzle became available in Canada in 2019, San Francisco-based Affirm in 2021, and in February, Swedish lender Klarna entered the Canadian scene. In June, Apple also announced the development of its own BNPL program through Apple Pay.

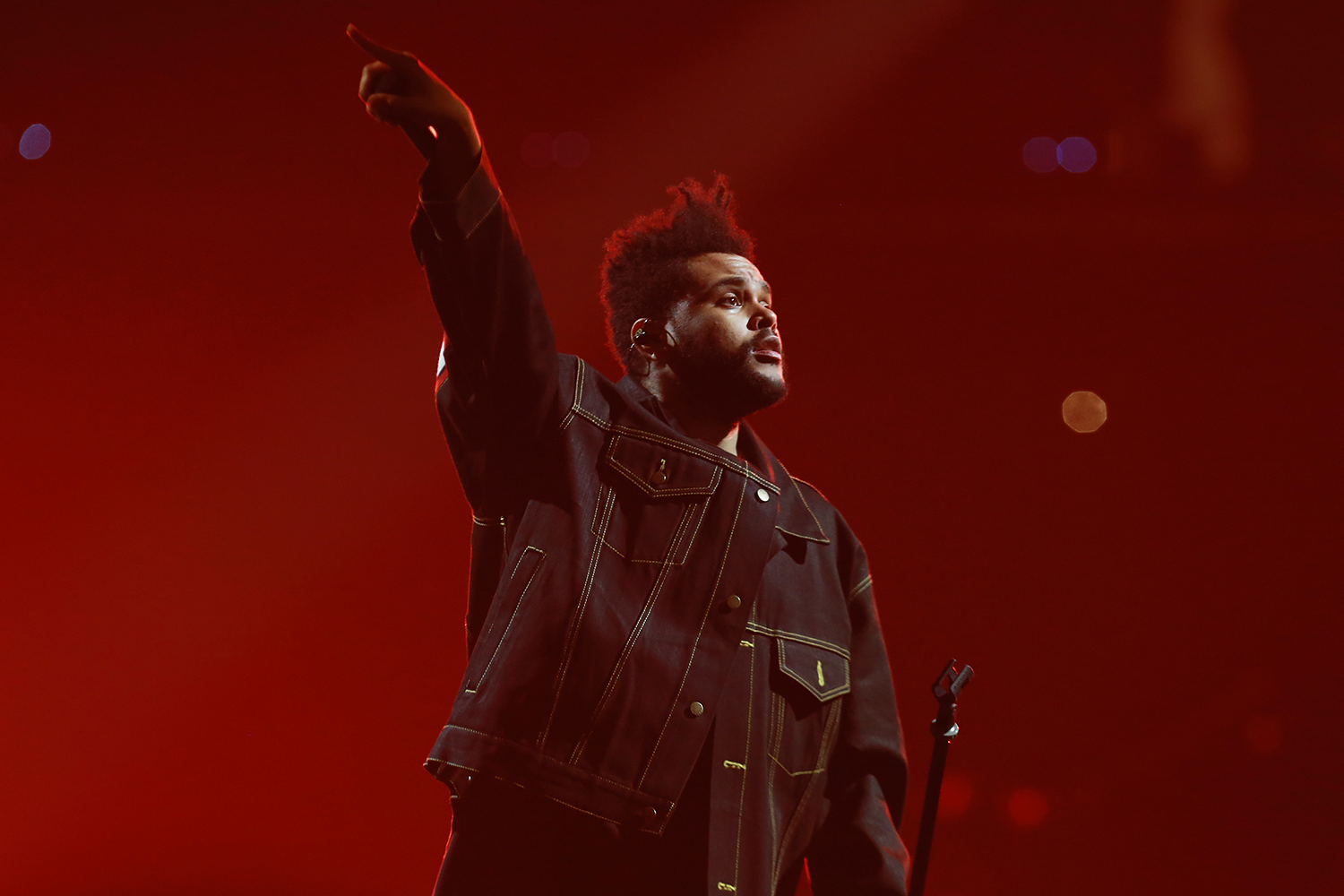

“There’s a lot of allure particularly from younger generations. They think, ‘Why would I pay the full amount now if I can pay a bit per month and not pay interest?’” says Brigitte Goulard, the head of Torys LLP’s consumer protection practice and fintech group, and the former deputy commissioner of the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, or FCAC. Research shows that BNPL users tend to be millennial or Gen Z shoppers: A recent FCAC study found the largest group is 18 to 44 years old, and data from the U.K. revealed 75 per cent of users are adults under 36. This is likely why companies are using influencers on TikTok and Instagram to promote BNPL platforms to shoppers, and hiring celebrities like ASAP Rocky and Ashley Graham as brand ambassadors.

Part of the BNPL allure is interest-free payments. Companies are able to offer zero interest to shoppers because they make their money by charging transaction fees to retailers—usually at a rate much higher than for credit card purchases, which are in the range of 1.5 to 3.5 per cent per transaction. Sezzle, for example, charges 6.1 per cent plus 30 cents per transaction, while Paybright’s rate is 8.95 per cent plus a 1.95 per cent credit card fee if consumers pay that way.

While these fees are hefty, BNPL has clear benefits for retailers, according to RBC Capital Markets research from November. It increases retail conversions an estimated 20 to 30 per cent and boosts average shopping basket amounts by 30 to 50 per cent. Affirm claims that its merchants report an 85 per cent increase in average order amounts when shoppers choose to use its BNPL plan over other payment methods, and that the platform increases repeat purchases by 20 per cent.

The risk of buy now, pay later plans for shoppers

For consumers, buy now, pay later isn’t without risks. Personal finance and consumer protection experts say that seeing the lower installment amounts can make shoppers perceive the price of an item as lower than it is. And unlike traditional layaway plans for much larger purchases such as appliances, which were once done in-store and required a lengthy application process, consumers have near-instant online approval at the point-of-purchase with BNPL plans; you typically don’t need a good credit score as most providers don’t run credit checks.

The FCAC said in a November pilot study of buy now, pay later platforms that these factors are a recipe for overspending and put consumers at risk of accumulating debt. The study, which surveyed more than 1,000 Canadians, found users commonly turned to the payment plans to address a “timing gap” when they didn’t yet have the funds for an unexpected purchase.

While 95 per cent of users in the study made their scheduled payments on time, 15 per cent of those respondents had made “unfavourable” financial trade offs to do so, such as delaying another bill, incurring an overdraft on their bank account or borrowing funds from friends and family.

Plus, buyers can face fees if they’re late making payments, or risk being declined for future loans with the BNPL provider. Goulard notes that while these loans don’t help consumers build their credit score, they can harm it in the event of late or missed payments.

To help buffer against improper use, BNPL providers say they don’t approve every order. Afterpay says on its website it checks whether a customer has sufficient funds on their card, the amount they have to repay and the number of orders they have open with the platform. Klarna performs either soft or hard credit checks depending on the payment plan the customer is signing up for. (Soft credit checks are for pre-approved offers and don’t impact your credit score or require your permission to execute. A hard credit check is for when the lender is assessing whether to give you a loan, which requires your consent and can impact your credit score.)

Shannon Lee Simmons, a certified financial planner and founder of the New School of Finance, cautions consumers to think carefully about whether they really want or need what they’re purchasing. While BNPL plans can be useful for necessary, emergency purchases, or used responsibly for budgeting reasons, she sees these platforms as part of the “extreme consumerism” culture that is driving rising debt levels and financial anxiety. “Consumer spending is really intense and people feel like they can’t keep up,” she says. Simmons says she’s seen the stress of her clients skyrocket after they buy something online that they later regret, often because they don’t think before they make the purchase—a mindset that BNPL options can encourage because shopping this way makes items seem cheaper than they are.

To avoid that financial anxiety, she recommends buyers calculate whether they can comfortably meet their installment payments, and pay their purchase off in a reasonable timeframe. It’s also important to keep track of when payments are due. Olaguera-Corcoran says she signs up for her buy now, pay later provider’s text alerts that warn her a payment is due a few days in advance and has set limits on how she uses these plans. The installment payment from a BNPL purchase has to fit into the “fun money” portion of her biweekly paycheque—about five per cent—and she has to completely pay off one purchase before considering another.

The pitfalls of BNPL has already attracted regulatory attention. Last year, the United States’ Consumer Financial Protection Bureau said it was opening an inquiry into BNPL platforms in December, and consumer groups in the U.K. warned the government against allowing the companies to self-regulate, as they had been, saying that the approach has been “woefully inadequate in curbing consumer harm.” (The British government announced it was strengthening regulation of BNPL agreements in June.)

In Canada, BNPL plans are already technically regulated as loans, with lenders obligated to disclose any interest or fees attached to the product. But Goulard says she still expects to see heightened regulatory interest in the country. While the FCAC study stopped short of recommending any additional regulatory action, it said it would coordinate with provincial and territorial oversight bodies to harmonize watch of these plans and foster consumer education.

Loans, mortgages and credit cards pose similar risks as buy now, pay later platforms, which is why they are regulated. For example, in order to get approved for a loan in Ontario, applicants need to prove their income, undergo a credit check and disclose debts. Still, that screening process doesn’t prevent huge consumer debt, Goulard says. What’s needed in tandem is greater financial education so people fully understand the risks of all financial products, including BNPL platforms. “There needs to be a higher awareness for consumers of how to avoid debt,” Goulard says.