Law Has a Diversity Problem. Can Start-up Firms Help Fix It?

After 10 years working on Toronto’s Bay Street, lawyer Ashlee Froese wanted something different. Although she was a partner at a leading mid-sized firm and had built a career in intellectual property law, she was disillusioned by the discrimination she both witnessed and experienced personally.

“When I was an articling student in 2005, I was working at a law firm and the ‘sage’ advice of my mentor, who happened to be a woman, was to cut my hair, dye it brown and to not wear high heels in order to be taken seriously,” says Froese.

Throughout her decade on Bay Street, Froese says she continued to encounter many colleagues who thought she didn’t “look like a lawyer” because of her long blonde hair and her style choices. Still, she stayed focused and became one of the first lawyers in Canada to specialize in fashion and social media law. When she decided to start her own firm, she knew it needed to be different: It had to reflect the city’s diversity—both in its staff and clients. She launched Froese Law in 2017 as a start-up style law firm specializing in branding and marketing law.

In a profession built on precedent, start-up law firms like Froese Law are helping create more diverse workforces by shaking up the traditional ways of operating often found at legacy firms. Young firms that understand the importance of more inclusive policies are reducing barriers for BIPOC and women lawyers by overhauling hiring practices and implementing tech in ways that make both practicing and accessing legal services more equitable. Start-ups can be prime environments for shaping culture as they are often small, nimble and tend to attract younger workers who are interested in changing the status quo.

“In the era of start-ups and social-media-led brands, the demographics of businesses that require legal services is drastically changing,” Froese says. “Diversity and inclusion were always important, but now we’re seeing that it can be detrimental to clients if firms aren’t equipped with lawyers that reflect the population.”

The business case for diversity

A lack of diverse legal representation can affect clients in many ways. Canada is a multicultural and multiethnic country with about 75 per cent of Toronto’s population made up of immigrants and second generation individuals, according to government data. As more Canadian workplaces, especially start-ups, work to better diversify staff, it’s vital that lawyers can better understand clients’ unique needs and advocate for them—especially when it comes to issues of discrimination, inclusion or equity in the workplace. Diverse legal teams bring diverse opinions, and can address problems in ways a like-minded group can’t.

A more diverse staff can also improve a law firm’s bottom line. One study by McKinsey & Company found that businesses who were in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity were 35 per cent more likely to make profits above the average in their industry. This in part is due to the fact diverse teams are a competitive differentiator from the “old boys club” seen at many organizations—a change that is attractive to clients.

“Small firms can play an important role in reimagining the old-school picture of who a lawyer is”

Even with widespread conversations about the importance of diversity in law—reports outlining recommendations to address systemic racism are not new—the numbers paint a picture that suggests progress is slow, if happening at all. People of colour are underrepresented in law firms in Canada, and racialized lawyers only make up 19.3 per cent of Ontario’s lawyers, according to 2016 data from the Law Society of Ontario (LSO). Less than four per cent are Black.

There are also fewer women in senior positions: Only 4.3 per cent of lawyers identifying as women in Ontario were partners as of 2018, compared to 12.4 per cent of men. What’s more, women make an average of $19,000 less a year than their counterparts who identify as men, according to a 2020 study. Racialized women face even greater obstacles when it comes to pay equity and leadership opportunities.

This long-standing problem starts at law schools. When Western University recently released photos of its law faculty’s new, overwhelmingly white advisory council, it sparked renewed attention on the issue. After facing criticism on social media from lawyers and students, the school released a statement that acknowledged “the legal profession has lacked diversity for far too long” and said it is committed to ensuring future classes better reflect the society we live in.

“Small firms can play an important role in reimagining the old-school picture of who a lawyer is,” says Rich Appiah, founder of the Toronto-based employment law firm Appiah Law. “I started my own firm in part because I wanted to stand out, to be the real ‘Rich Appiah’ on my own terms and on my own timeline.”

Reducing systemic barriers that prevent people from entering law

Appiah’s experience as a law student in the early 2000s showed him firsthand how the industry favours certain people while putting others at a disadvantage. One stark example was on-campus interviews and recruitment dinners, a tradition where graduating students meet and dine with lawyers in the hopes they get hired at their firm. The practice has been critiqued for catering to candidates who are white and upper-class. In other words, people who look like many of the lawyers doing the hiring. For Appiah, it was exactly that.

“The question of inclusivity and diversity in law engages the concept of gender norms and racial norms, but it also engages class. I’m a brown guy from Hamilton who came from a poor family: I didn’t attend a private school; I didn’t attend fancy dinners; and I didn’t schmooze with the ‘bigwigs,’” Appiah says. “I worked hard, but I found myself at a disadvantage and insecure when I participated in firm recruitment processes in law school. I never forgot that.”

Some law schools have tried to rectify this in recent years. Western University’s faculty of law offers free LSAT prep courses, application support packages for Black and Indigenous students, and financial support, like scholarships. At the University of Toronto, the Black Law Students Association offers resources and support, including mentorship with Black lawyers, to help increase the number of Black law professionals.

“The question of inclusivity and diversity in law engages the concept of gender norms and racial norms, but it also engages class”

Now that he’s the one doing the hiring, Appiah works to ensure people feel like they belong in law. Rather than continue the “wine and dine” practice that made him feel so uncomfortable, Appiah intentionally designed his own hiring process to level the playing field for all applicants. His firm has a four-step screening practice that includes asking candidates the three most important qualities of a labour and employment lawyer and how they have demonstrated these qualities, two in-person interviews and a timed “exam” where candidates are presented with scenarios and provide responses on how they’d handle them. The goal is to understand candidates’ strengths and weaknesses, but also who they are as people, in order to build an inclusive business.

“When I started my firm, I decided that inclusiveness was going to be a firm state of being, and not just an initiative requiring a checkbox,” he says. “Practically, I understood that that meant that I would consider anyone for a job—even if they didn’t look like me, share my gender, speak like me or even share my interests.”

Making the legal field more welcoming to women

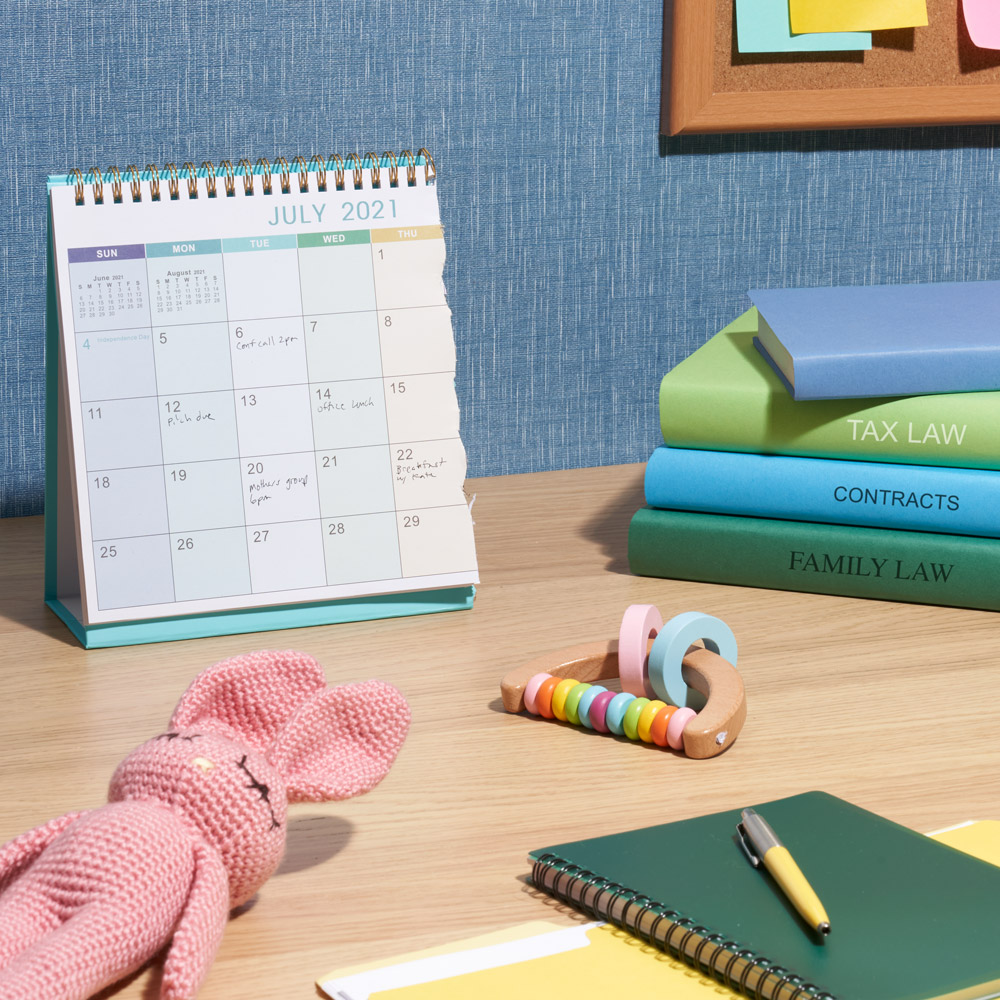

Research shows that women often face a “maternal wall” in their careers, which refers to the negative implications that family obligations can have on leadership opportunities. At Froese Law, the workplace is designed to reduce common barriers working women face by utilizing tech.

The office is paperless—staff rely on legal software and video meetings—so remote work options are available to everyone. For Froese, this policy was an important step in moving away from traditional law’s rigid structure—long, in-person hours at downtown office buildings—and a way to create space for people with personal lives that require more flexibility, like a single parent or caregiver. The firm also allows associates with children to block off time in the mornings and afternoons for childcare needs such as school drop-offs.

“People do their best work when they are happy and supported”

This is important as new research from McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace report shows women are more like to experience burnout. But when they’re working for supportive bosses and companies that prioritize diversity, equity and inclusion, they have better professional outcomes. “People do their best work when they are happy and supported, and that’s what’s important to me—my team being happy and producing high-caliber work,” says Froese.

Making legal services affordable for the average Canadian

Technological advancements have also diversified who can afford access to legal services by changing how they are offered. Brett Colvin got the idea to found Goodlawyer, an online platform that connects entrepreneurs with lawyers based on their needs, when he was working as a corporate attorney at Borden Ladner Gervais. There, he realized that he would be unable to afford his own hourly rate. “Bloated billable hours and the intimidating prospect of hiring a lawyer leave countless business owners without the legal help they need,” he says.

He launched Goodlawyer in 2019 in an effort to increase access to quality legal services by providing an on-demand, “a la carte” legal services marketplace that allows business owners to get professional support at a fraction of traditional firm rates.

Goodlawyer is one of many start-ups specializing in legal software that have developed programs using artificial intelligence, automation and data analytics to help attorneys cut costs for firms and clients, making legal services more affordable. Kira Systems, a machine learning program that helps attorneys analyze contracts, is one example. CiteRight, a platform that simplifies the e-filing process for Canadian courts, is another. Similar to Goodlawyer, these technologies streamline the legal process, create more efficiency and reduce costs.

“The legal sector is in an extremely interesting state of flux right now”

Improving access to legal services is not only important to young entrepreneurs, but also to marginalized members of society and people of colour. These groups continue to face barriers when it comes to obtaining legal advice or representation. In Canada, the amount of people representing themselves in civil or family court cases has risen over the past decade as more people struggle to afford a lawyer—a situation worsened by the pandemic’s impact on individuals’ earnings.

“Dating back to law school, I’ve had a keen awareness of the access-to-justice crisis,” Colvin says. “According to legal software company Clio’s legal trends report, roughly 77 per cent of legal needs in North America go unmet.”

Can these changes happening at start-ups influence bigger firms?

While not a cure-all for long-standing inequity issues, the cultural shifts modelled by start-ups can influence corporate sectors. More institutions including universities and law firms are speaking out about the need to improve the industry. Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives are becoming more common, and clients are starting to demand better representation in the firms they hire. In the U.S. and the U.K., big-name clients like Facebook and HP are telling legacy firms they’ll take their business elsewhere if gender and racial diversity doesn’t improve.

Research shows that nearly a quarter of the work done by lawyers can be automated using technology—and firms that are equipped will end up ahead of the ones who are slow to change. “The legal sector is in an extremely interesting state of flux right now, with legal technology slowly bringing about changes that are long overdue,” says Colvin. “It is hard to find a sector more ripe for disruption.”