The Problem With Rogers Could Get a Whole Lot Worse if It Acquires Shaw

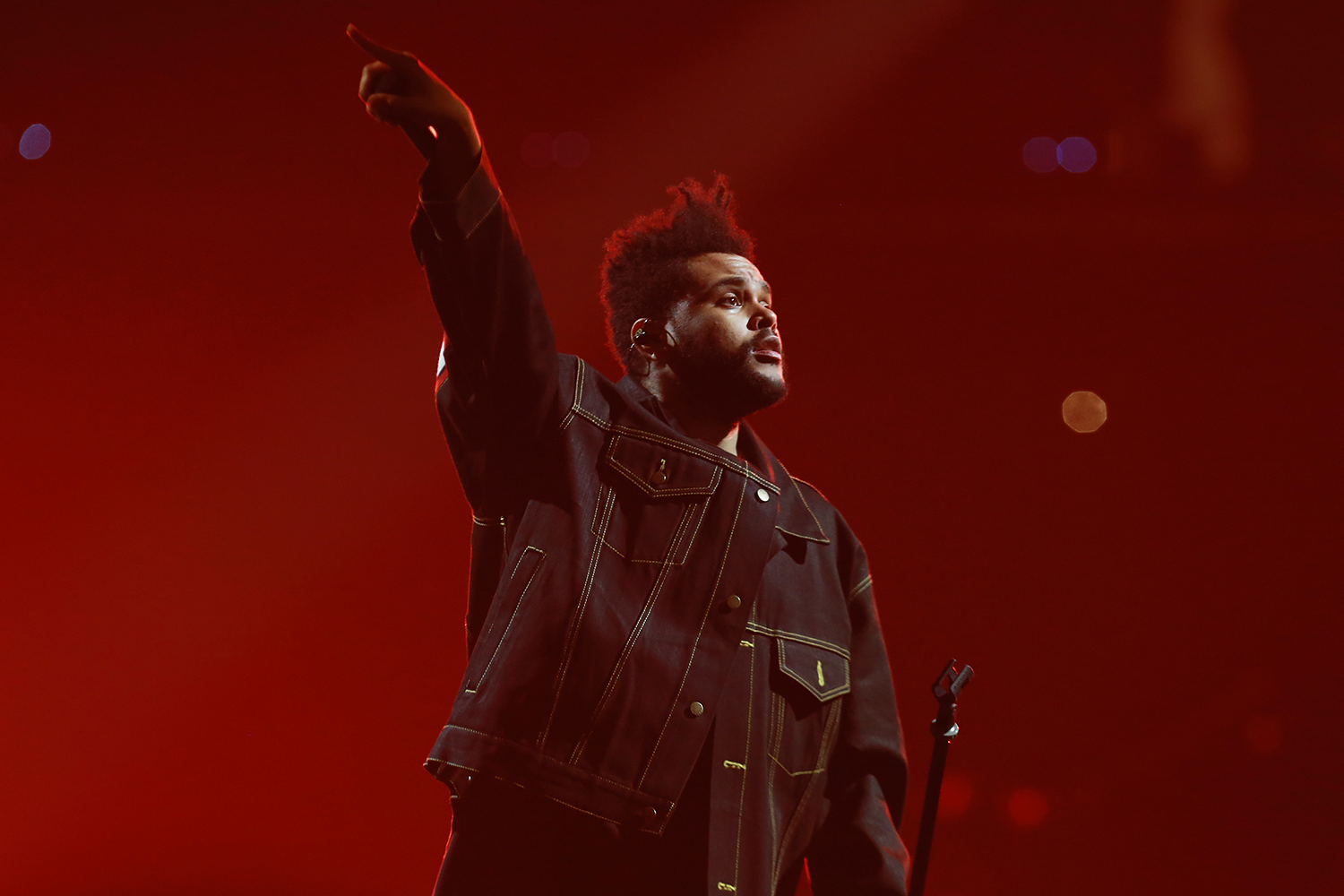

Last Friday was a rough day for many Canadians. The nationwide Rogers outage stopped phone and internet service for around 12.2 million customers, affected debit payments, transit systems, and emergency services and even forced The Weeknd to postpone the first stop on his world tour at Toronto’s Rogers Centre. Rogers says a “network system failure” after a “maintenance update” caused the problem.

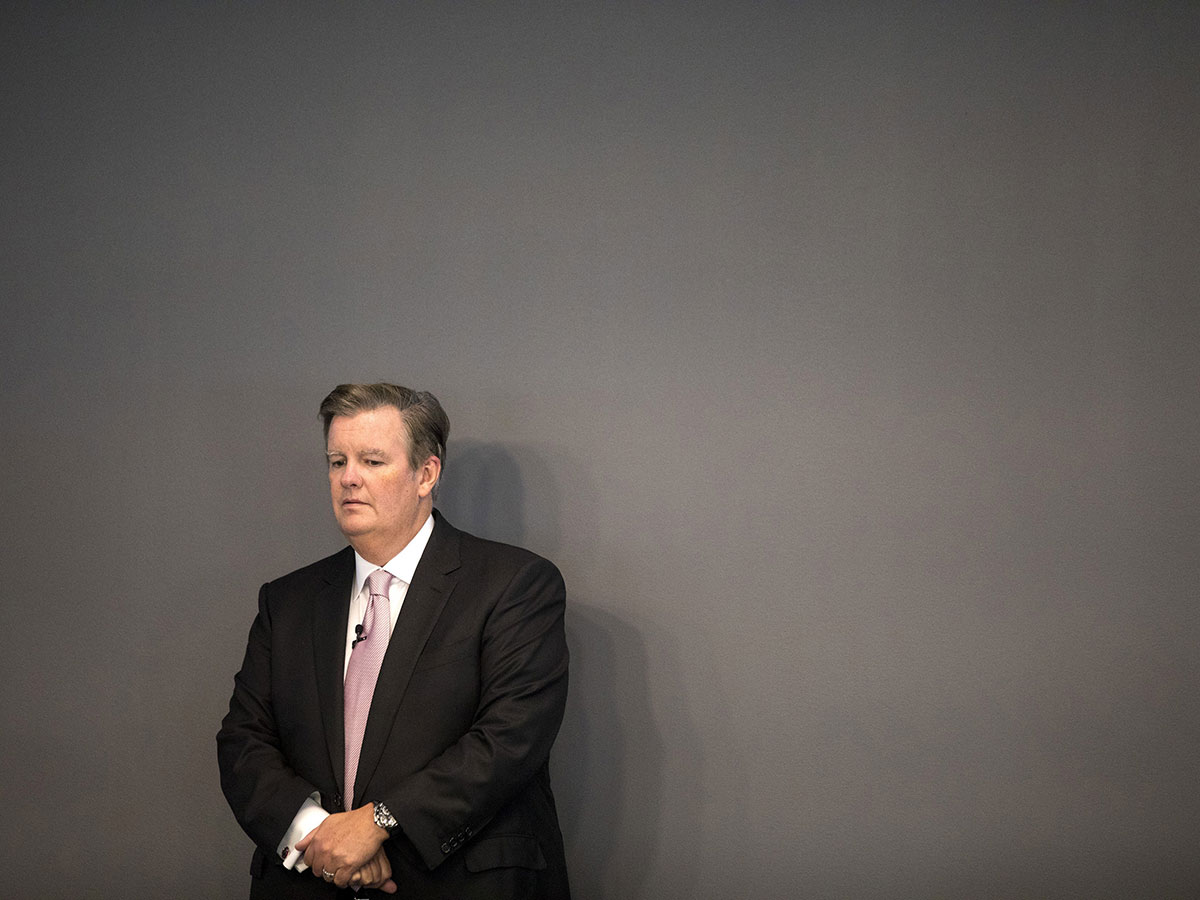

The outage was terrible timing for Rogers’ proposed $26-billion takeover of Shaw Communications—one of the largest telecom providers in Western Canada—as it happened days after the telecom giant met with Canada’s Competition Bureau to discuss the deal. While the Rogers-Shaw transaction got the thumbs up from the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, or CRTC, the competition watchdog is trying to block the merger, arguing it would result in fewer telecom choices for Canadians and higher bills. The takeover would give Rogers, one of the country’s largest wireless providers, a bigger slice of Canada’s market. (The merger awaits a final verdict.)

Experts say the outage, which cost some small businesses thousands of dollars in lost sales, highlights the issue of allowing a single company to have so much power over a critical industry. Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor control about 90 per cent of Canada’s telecom industry. “When we are beholden to gigantic companies and one of them fails, millions of people across Canada suffer,” says Rosa Addario, communications manager for OpenMedia, a non-profit organization that advocates for an open and affordable internet.

A Rogers-Shaw merger could affect customer choice and pricing

The system failure is causing more people to question whether Rogers should have an even greater hold over Canada’s telecom market. In March 2021, Rogers agreed to buy Shaw, which owns Freedom Mobile and Shaw Mobile in Alberta, B.C. and Ontario. The deal, if approved, would combine two of Canada’s biggest telecoms in the sixth-largest merger in Canadian history. Even though Rogers agreed to sell Freedom Mobile to Quebecor to appease competition regulators, if the Rogers-Shaw transaction goes through, the prices and selection of services available to Canadians may worsen.

David Soberman, a marketing professor at the Rotman School of Management, explains that the big three competitors in Canada—Rogers, Bell and Telus—often raise their prices in lockstep, so there’s little difference in the deals offered to customers.

If Bell, for example, reduces its prices in the short term, it may pick up some customers from Rogers and Telus. “But essentially Rogers and Telus would match that price reduction, so market share would stay the same,” says Soberman. He says there’s currently not much incentive for telecoms to slash costs in the long term, as Rogers, Bell and Telus would be making less money if they all lowered prices.

The lack of competition is reflected in the amount of money we pay for telecom services. Canada has some of the most expensive cell bills in the world: It costs about $144 for a 4G cell phone plan with at least 100 GB of data per month, the highest out of more than 40 countries tracked in a 2021 Rewheel report.

And because many people bundle their services—cell, internet and cable—with a single provider to save money, when one provider goes down, it affects more than wifi. “We can’t condemn Bell and Telus because they haven’t had these problems, but Rogers has had the problems twice within 14 months,” says Soberman, referring to the recent previous Rogers outage. As a result, François-Philippe Champagne, the minister of innovation, science and industry, said the big providers must enter into a formal agreement to offer back-up services to each other should outages happen again.

In addition to little competition in our telecom sector, part of the problem, according to Michael Geist, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, is a lack of consumer protection rules to refund customers in case of outages. Even though Rogers said it would compensate customers for five days of lost service after many customers complained, Geist doesn’t think it’s enough—especially since some people were not able to call 911. “If we had clear, regulated [compensation] minimums that better reflected the actual harm that occurs when services are lost for an extended period of time, at least consumers would be better compensated when this takes place,” he says.

Learning from previous telecom mergers

When asked about how a Rogers-Shaw merger might affect Canadians, Geist and Addario point to the past. In 2017, Bell bought MTS, the largest wireless provider in Manitoba, in a $3.9-billion deal. At the time, consumer advocacy groups raised concerns that the merger would result in higher prices and a reduction in the number of telecom choices for customers. Bell hiked prices on most of its services almost six months after the deal closed.

“Any time you lessen the amount of competition in the marketplace and increase consolidation, it has a negative effect on consumer choice and a likely long-term increase in costs,” says Geist. “The long-term effect of Bell taking over MTS was decreased choice and increased prices.”

According to experts, the government needs to embrace a more competitive and diverse telecom sector by reducing market barriers. Geist says regulators have been reluctant to embrace innovative solutions, such as mobile virtual network operators, or MVNOs, which rent out the infrastructure of existing networks and offer customers access to large network coverage without the premium prices. MVNOs are popular in the U.S. but aren’t allowed in Canada due to a 2021 CRTC ruling requiring operators to own some of their wireless infrastructure. (Canadian actor Ryan Reynolds runs an MVNO called Mint Mobile in the U.S. and has tried to bring it north of the border.)

“One of the most important ways that you can actually create competition within an industry is to not have regulatory barriers to new entrants,” says Soberman. “If I decided I wanted to open my mobile network in Canada, the CRTC would have to approve my application, and I would have to build a network.”

All of that red tape is time- and capital-intensive. So, where do we go from here? Addario explains that Canada needs comprehensive competition law reform. “That will allow low-cost carriers to enter the market and loosen the stronghold that the big three has over our market.”