Is Collecting Consumer Data a Bad Thing?

In 2020, more than one million Canadians used Tim Hortons’ mobile app to order their morning coffee. What they didn’t know was that the app was collecting their location data, even after they’d closed it. The federal privacy commissioner’s report from June 2022 found that the coffee chain had violated privacy laws, and the whole mess put a spotlight on the thorny issue of consumer-data collection.

Here, Sharon Bauer, founder of Bamboo Data Consulting, and Oshoma Momoh, chief technical adviser at MaRS Discovery District, discuss how consumer data can help businesses—and how it can be collected responsibly.

SHARON BAUER: There’s nothing wrong with gathering location data for marketing and discounts if you get permission to do so. But Tim Hortons gave the impression that its app only collected data when customers were using it. If a user had known that the app would track them wherever they went, they might have felt differently about whether that value exchange was worth it.

OSHOMA MOMOH: Companies are realizing that they have to focus on privacy and ethical data collection. If a business collects data, it should be to improve customer experience over time. They might ask questions like “What products do my customers like best? Are there customer segments that are underserved or new customers I could reach through targeted advertising?” There’s also data collection that personalizes the experience, like how Amazon remembers that you looked at a certain product. We’re seeing more applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence to tailor the experience to the consumer.

S.B.: Consumers are often willing to give up their data in exchange for something, like a personalized experience or discounts. Privacy can be a perk as opposed to something that hinders the bottom line. Companies can design their products and services with privacy in mind. Just-in-time consent, where companies ask the user for their information at the moment it’s needed, is a good example of this. The user can make a decision in context.

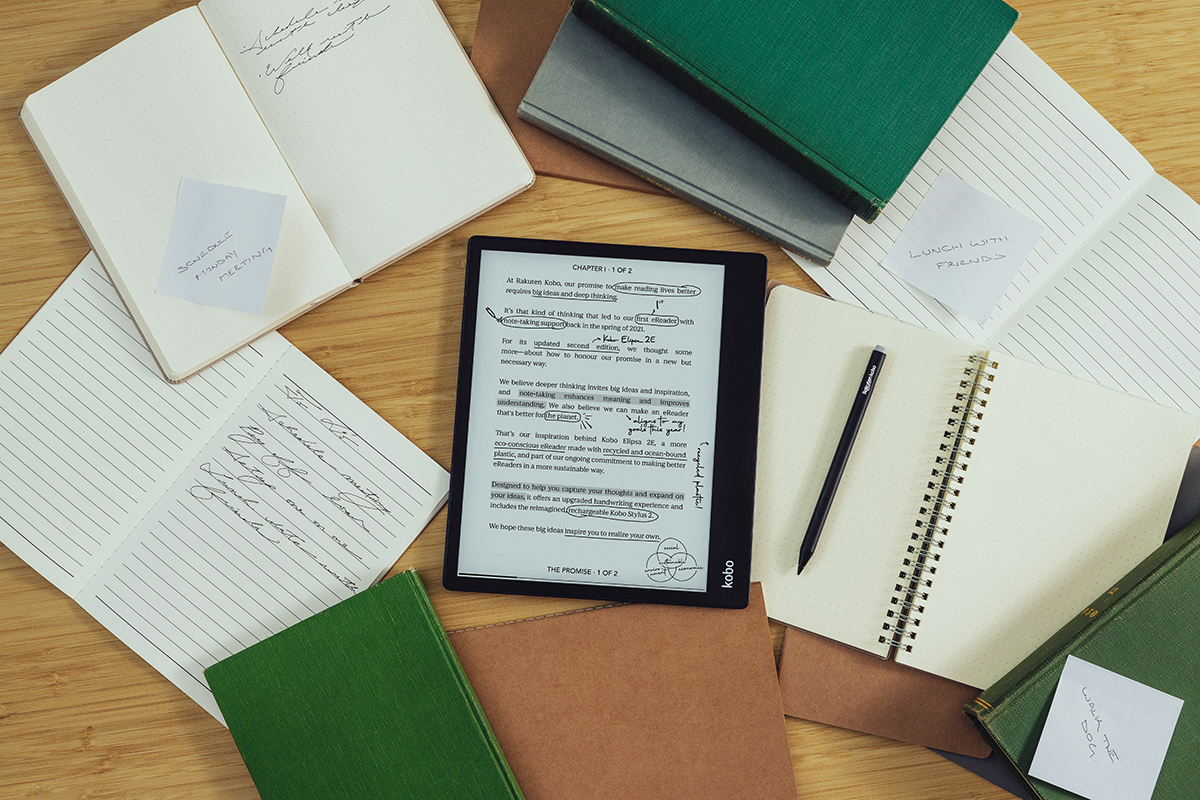

O.M.: One app that does privacy right is 1Password, a password-manager app I’ve been using for years. It can check to see if any of the websites you use have been breached. But it only does this when and if you give it permission to do so. When it comes to long-term services, check-ins and reminders are necessary. For example, I appreciate hearing from Google once in a while to learn what it’s doing with my Gmail data. But the experience isn’t perfect. A lot of times, you get a pop-up asking for your permission with an escape hatch to the privacy policy—“for more information, go to this link.” If you’re not okay with the five-second prompt, you’re signing up for a 15-minute legal read.

S.B.: Companies should make their privacy policy more user-friendly, with video, infographics or other creative ways of displaying their practices. August, a digital marketing company, has a brilliant one—it’s attractive and easy to understand. It’s like a story, and you just want to keep scrolling down the page.

O.M.: If a company does a good job of data collection, it can get better customer engagement, generate more revenue and have more repeat business. For example, if you’re signing up for a service that has a geographic component, the experience is better because the app knows your location. Conversely, if a company doesn’t do those things well, it’ll get all the opposites.

S.B.: In order to collect meaningful consent, whether explicit or implied, a company must be transparent about what they’re collecting, how they intend to use it and whether they intend to disclose that data to a third party. The federal government’s forthcoming privacy legislation, Bill C-27, will have a lot more teeth to it. Regulators will have more power, and a new tribunal will be able to levy hefty fines. If you have a good program that’s already compliant with Europe’s general data and protection regulations, I don’t think it’s going to be a significant change. But for companies that have no privacy program, it’s going to be a heavy lift. They’re going to have to demonstrate that they have both the policies and a culture where their employees comply with them.